120 Years Ago: The Klondike Gold Rush

Seattle Post-Intelligencer Saturday, July 17, 1897

This month marks the 120th anniversary of the Klondike Gold Rush. Immortalized in the works of author and gold seeker Jack London, the gold rush in Canada's remote Yukon territory captured the imagination of an America mired in the depths of a deflationary depression.

Spurred on by newspapers trying to one-up their competition with tales of fortunes found in the Great Frozen North, over 100,000 men abandoned their homes and families to follow their dreams of striking it rich. Unlike previous gold rushes in California and Western Australia, these fortune hunters would have to wrest their riches from a hostile land of ice and bitter cold.

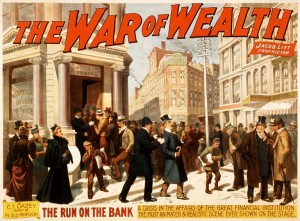

The Panic of 1896

To understand the grip the Klondike Gold Rush had on the American psyche, one must understand the economic conditions of the time. The United States had been gripped in a deep deflationary depression since 1893. Hundreds of banks had failed. Unemployment was over 14%. The stock market had collapsed. Thousands of businesses had gone under. By 1895, the US government was running out of gold to back the dollar, causing even more people to redeem their greenbacks for gold. This gold was either kept or exchanged for gold-backed foreign currency, removing it from the US economy. So, when news broke in the summer of 1897 of millions of dollars of gold just lying in the creek beds of the Yukon Territory, thousands of disillusioned men dropped everything and headed to Alaska.

Called "stampeders", an estimated 100,000 men embarked on the Klondike Gold Rush. Of those, roughly a two thirds turned back before getting to the gold fields. Of the ~30,000 who made it to the Klondike River, only 4,000 found gold. Out of those 4,000, only a few hundred became rich.

Yukon Gold

Gold was first spotted (by Europeans) along the Yukon River in 1830s, but due to the harsh conditions and small deposits, these first reports weren't acted on. In 1878, George Holt returned from a trip to the area with gold nuggets large enough to garner attention. Small-scale gold prospecting began, centered around placer deposits on the shores and sandbars of the Yukon River. Some 200 men were working the Yukon valley by 1883. The tiny town of Forty Mile, named for the distance to the nearest fort, was founded to supply the miners with provisions and provide a place to record their claims.

Gold deposits in the Yukon Territory were small and scattered, dampening the enthusiasm of many would-be gold miners. This all changed on August 16, 1896.

August of 1896 found American prospector George Carmack hunting for gold in the creeks that fed into the Klondike River. Accompanied by his native wife, brother-in-law Skookum Jim, and nephew Tagish Charley, Carmack was following a lead from another prospector to search around Rabbit Creek. What they found was the stuff of legends. The creek was full of gold! The deposit was far beyond anything that had ever been discovered in the area.

Carmack quickly laid out four claims along the creek: Two claims for himself (one regular, one for being the one who discovered the deposit), one for his brother in law, and one for his wife's nephew. He then started the 50-mile trek to officially file their claims with the registrar at Forty Mile before anyone else found out.

Klondike Fever

Word quickly spread among the mining communities in the Yukon valley. Prospectors rushed to the Klondike River to stake out the best claims before word got out to the "outside world." Harsh weather conditions and iced-over rivers meant it would take months for the news to reach Seattle and San Francisco.

Even so, word of the enormous gold discovery began circulating in the Great White North. Braving sub-zero temperatures, prospectors in northern Alaska and Canada loaded up dog sleds and headed south to the Klondike before the best claims were taken. Many of the few who heard of the gold discovery discounted it as fantasy. How could such a rich gold strike possibly be true?

The Great Klondike Gold Rush really began when the ice thawed in 1897, and two steamers loaded with gold-toting Klondike prospectors hit the West Coast. The steamer Excelsior arrived at San Francisco on July 14, 1897. Her 30 passengers were said to have brought a total of $500,000 in gold with them ($13.6 million in 2015 dollars). Three days later, the steamer Portland arrived in Seattle. The 40 miners aboard reportedly had more than $1 million of gold ($27.2 million in 2015 dollars) between them. The reaction of the public was explosive.

Getting To the Klondike Gold Fields

The Yukon River flows northward 1,980 miles from its headwaters in British Colombia to the Bering Sea. River travel is only possible for three months, between July and September, before the river ices over for the rest of the year. With temperatures as low as -50°F, overland travel during the winter was often fatal. Conversely, travel during the summer often meant slogging through mud that sometimes could reach up to the waist.

![By National Park Service [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://cdn-img.gainesvillecoins.com/blog/2019/07/klondike_routes_map.jpg)

National Park Service

Oversea Route to Klondike

The well-to-do prospector heading to the Klondike could take a ship from Seattle (934 nautical miles, 1,075 mi) or San Francisco (~2,625 nautical miles, 3,020 mi) around the Aleutian Islands to the mouth of the Yukon River where it emptied into the Bering Sea. From there, it was another 1,600 miles or so by flat-bottomed boat up the Yukon to Dawson City, the center of the Klondike Gold Rush. Many of the flat-bottomed river boats came to grief during the dangerous trip to Dawson or back, leaving hundreds of prospectors trapped on the coast of the Bering Sea when the river froze over in 1898.

Before gold was discovered, the trip to the mouth of the Yukon cost an average of $150 ($4,100), but the first navigation season after the gold rush began saw tickets go for $1,000 ($27,276) or more.

Overland Route to Klondike

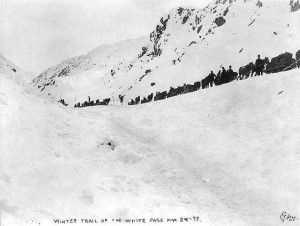

Stampeders climbing the final mile of the Chilkoot Pass

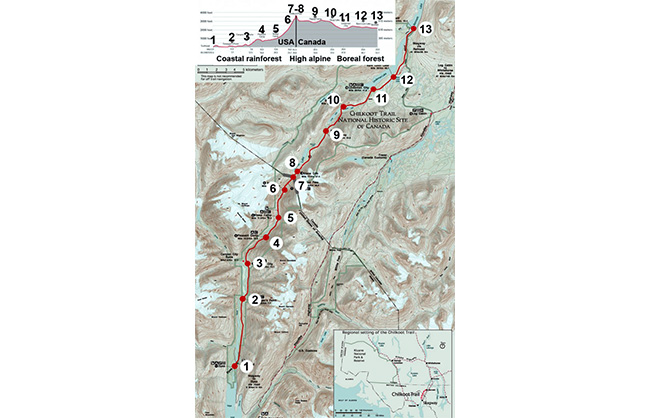

Stampeders climbing the final mile of the Chilkoot PassThere were two main land routes to the Klondike Gold Fields, both located in the northernmost fjord of Alaska's Inside Passage. Dyea (Chilkoot Trail) and Skagway (White Pass Trail) were only four miles apart at sea level, each at the base of its own trail up Alaska's Coastal Range to end at Lake Bennett. the headwaters of the Yukon River.

The Chilkoot Pass summit is 3.501 ft above sea level over 33 dangerous miles by foot. The White Pass climbs to an elevation of 2,640 ft over the course of 40 miles. Climbing either was an arduous task in either summer or winter, but every would-be gold prospector had to climb them dozens of times to get their supplies over the mountains.

Some Canadian stampeders from Alberta and British Columbia used one of the lesser-known "All-Canada" routes, which turned out to be as worse, if not more so, than the overland routes from Alaska.

No route was a straight walk. The paths wound through gullies and ravines, and it was easy to lose one's way during one of the massive blizzards that barreled down the passes.

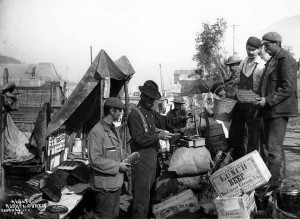

The Klondike Ton of Goods

Faced with the prospect of tens of thousands of ill-prepared gold seekers dying in the harsh Yukon winter, the Canadian Government set requirements for entry into the country. Every Klondike Gold Rush stampeder had to bring one year's supply of food, measured at 3 pounds per day. This totaled a little more than 1,000 pounds. The addition of necessary supplies such as clothing and prospecting tools brought the total weight per person to approximately one ton. The average cost for the "Klondike ton of supplies" started at $500 ($13,600), but prices rapidly rose.

Any goods purchased in the US and brought across the border at Chilkoot Pass and White Pass were subject to heavy customs duties. This nearly sparked a riot among thousands of American would-be prospectors, but the North West Mounted Police soon arrived in force, setting up Maxim machine guns at the head of the passes to keep the peace.

That first summer, $174,000 in customs duties were collected by Canadian customs houses at Chilkoot and White Pass, over $4.6 million in 2015 dollars!

The above expenses did not count the cost of getting the goods to the goldfields. Beyond the shipping cost from Seattle or San Francisco to Alaska, those gold seekers taking the land route had to pay to have their provisions guarded at both ends as they carried it to the top of the mountain pass, one backpack at a time. Those who could afford it hired laborers called packers at 50 cents ($13) a pound to carry their supplies up the treacherous slopes. Fares rapidly escalated, as bidding wars broke out between well-to-do prospectors

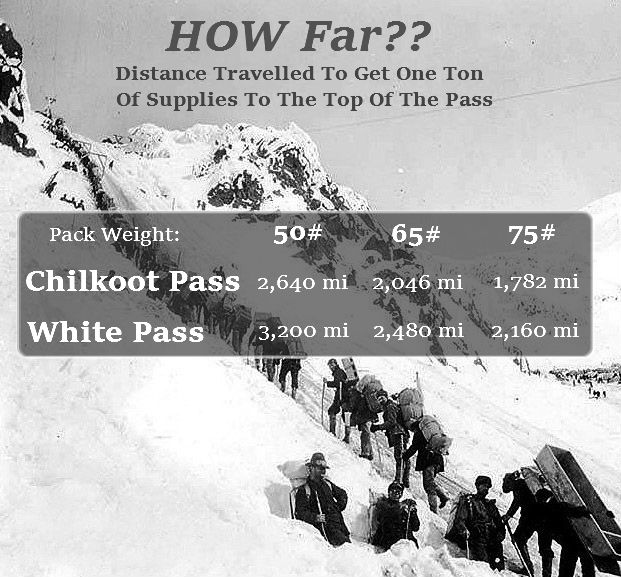

Klondike stampeders had two options when battling the Chilkoot or White Passes: Lighter packs but more trips, or heavier packs and fewer trips. With a 50-pound pack, it would take 40 trips back and forth to hump the required 2,000 pounds of supplies to the top of the pass. In return for more hardship in making the journey up the steep paths, 65-pound packs would cut the round-trips down to 31. For the masochists, lugging a 75-pound pack would only take 27 trips up and down, but the penalty for hauling half again more than a 50-pound pack would come in exhaustion and a greater chance for injury.

Looking at the chart, one would wonder why anyone would take the White Pass over the Chilkoot pass. The answer can be summed up in two words: Pack animals.

The White Pass, although steep, had a gentler grade at the expense of a longer length. That meant pack animals could be used to carry supplies to the head of the pass, which could more than triple the weight carried per trip (assuming the stampeder also carried a pack).

Skagway merchant and packer Joe Brooks is another man who made his fortune while never seeing the gold fields. Owner of an eventual 335 pack mules, Brooks made $5,000 a day ($136,400) at the height of the gold rush.

The demand for pack animals soon meant that horses had become scarce on the US West Coast down to San Francisco. Most of these horses, already broken down or sick, were driven up and down the narrow muddy paths of the White Pass trail until they died. They were then tossed over the cliff, or left to rot where they collapsed. Over 3,000 pack animals died this way, and the stench flowed down the valley to envelope the town. Author Jack London dubbed the area "Dead Horse Trail" after experiencing the results first-hand.

Chilkoot Pass

Photo showing the much gentler slope of the Golden Stairs

The Chilkoot Trail had been used for centuries by the local Tlingit first nation to trade with other tribes in the interior. As it was seven miles shorter than the White Pass trail, it was initially the more popular choice for the land route to the gold fields. Before the Klondike Gold Rush, the few miners already working small deposits used the trail to travel to civilization and back.

The Chilkoot Trail started at sea level, and ended at an altitude of 3,501 ft. However, the last part of the trail was extremely steep, rising a slippery 1,000 ft over 1/2 mile. The first gold seekers soon christened the trail "The Meanest 33 Miles In History." The steepness of the Chilkoot Trail meant it was impossible to use pack animals to transport goods. It also meant rockslides and avalanches were common.

Present-day hiking map of Chilkoot Trail, with elevations (National Park Service)

Present-day hiking map of Chilkoot Trail, with elevations (National Park Service)Again, where there is money to be made at the expense of gold prospectors, someone soon arrives to take said money. Stampeders arriving at the Chilkoot Trail in the winter of 1898 found a "VIP line" near the end of the pass. Called "the Golden Stairs," 1,500 steps had been chiseled into the ice at a 45% slope to the top of the pass, with guide ropes on either side. For a fee, one could use the single-file stairs to carry a pack to the summit, then use an ice slide built into the mountain next to the stairs for an "express trip" back to the base of the stairs.

While the path up the Golden Stairs was technically longer than the regular route, it was practically a cakewalk compared to the mud and mire of "Hell's Half Mile." Those who afford to take the Stairs did so.

White Pass

While the Chilkoot Pass had been in use for hundreds of years for trade between First Peoples tribes, White Pass was only discovered by Europeans in 1887. To preserve their monopoly on travel between the coastal areas and inland tribes in the pre-European era, the Chilkoot had closed off White Pass, killing anyone who tried to use it. Eventually, only rumors of another pass survived.

White Pass 1899

White Pass 1899William Oglivie discovered White Pass in 1887 while conducting a survey on behalf of the Canadian government. With a summit at 2,864 ft, White Pass was far easier to traverse than Chilkoot, and plans were immediately hatched by William Moore, who was a member of the expedition, to build a wagon trail to the Yukon.

The same year, Moore established a town at the mouth of the Skagway River. He was confident that a big gold strike would be discovered in the Yukon sooner or later, and the deep water harbor at Skagway would make it the gateway to the gold fields. It took years of work to make the White Pass trail passable by pack animals, but the two-foot width in several locations precluded the use of wagons.

At the height of the Klondike Gold Rush, construction of a narrow-gauge railroad at Skagway began. Carved from the mountainsides with hand tools and dynamite, the White Pass & Yukon Railroad took two years, tens of thousands of workers, 450 tons of dynamite, and $10 million to complete. But by the time the railway opened in 1900, gold had been discovered in Nome, and the Klondike Gold Rush was winding down. The railroad lived on as a freight line into the Canadian interior, and conducts special trips using an original steam engine during the vacation season.

A portion of the original White Pass Trail used by stampeders in 1897-1899 can still be seen today near the top of the pass, untouched since the Klondike Gold Rush.

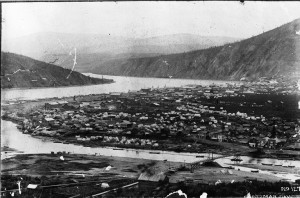

Dawson City - Klondike Gold Rush Capital

Dawson City was the epicenter of the Klondike Gold Rush. Located at the confluence of the Yukon and Klondike Rivers, Dawson was 550 treacherous miles down the Yukon River from Lake Bennett by self-built boat or raft, some of which could carry more than 200 people. Dawson was the destination of thousands of stampeders, and hundreds lost their lives on this final leg of the journey.

To get to Dawson, the gold-seekers had to navigate a large whirlpool in Miles Canyon and the deadly White Horse Rapids. Swift currents at every bend could slam the boats of the inattentive or inexperienced into the rocks, and sandbars lurked just beneath the surface to upend any craft unlucky enough to strike them. Boats, either alone or in flotillas, had to regularly stop to build a fire on the riverbank to warm up, else freeze to death.

Numerous fatalities soon had the North West Mounted Police requiring every boat to be numbered before leaving Lake Bennett, with the identity of all aboard recorded in order to notify the next of kin (if needed). Once a party reached White Horse, they were required to hire an experienced river pilot to navigate the deadly rapids.

True to the entrepreneurial spirit of those who saw a need to be filled, Norman Maccaulay built a wooden-railed tramway at White Horse that ran from the riverbank just above the rapids, and ended just below. For the price of $25 ($682), your boat and supplies would be safely conveyed past the murderous rapids.

Those who successfully made the journey soon drove the population of Dawson to more than 30,000 people, making it the largest town on the West Coast north of San Fransisco, if only for a little while. At the height of the Klondike Gold Rush, a city lot cost upwards of $10,000 ($8 million). Prime lots located on Front St, the main road through Dawson, cost $20,000 ($16 million. A small log cabin rented for $100 ($2,700) a month.

A large presence by the North West Mounted Police kept the peace, leading to Dawson being considered the safest place in the Yukon Territory. Dawson was the first town in Western Canada to have electric lighting. After the great fire of 1899 burned down more than 100 buildings, a system of fire hydrants was installed along the streets. By the end of the Klondike Gold Rush, Dawson had telephone service and four newspapers. The town still stands today, focused on gold rush-themed tourism and casino gambling.

Stories Of Privation

Just a few months after the first news of gold in the Klondike, disappointed fortune seekers who thought they were going to be instant millionaires were turning their backs to the Alaskan frontier. For many, one look at the Chilkook Pass and the thought of carrying supplies up that slope was enough for them to cash out and head back home. Others made it part-way through the trip before giving up, and others arrived in Dawson City to find all the mining claims taken.

The first wave of gold hunters in 1897 crossed into Canada before the Mounties could establish order. Dawson City was soon flooded with an estimated 14,000 men, women and children. Many had scant provisions or money.

Charlie Chaplin's "Little Tramp" is forced to eat his own shoe to survive the Klondike winter in 1925's "The Gold Rush"

Charlie Chaplin's "Little Tramp" is forced to eat his own shoe to survive the Klondike winter in 1925's "The Gold Rush"At the same time as these thousands of ill-equipped gold seekers flooded the area, experienced prospectors who had made their fortune the previous winter were leaving their claims on the Klondike to flee starvation.

One old hand noted that by the time he left, both general stores in Dawson had been closed for six weeks from a lack of merchandise, and "not a pound of provisions" could be found. The situation became much more deadly in the winter of 1897-1898. Sickness, starvation, and "cabin fever" in sub-zero temperatures claimed many lives.

The image of the starving would-be Klondike gold prospector became part of popular culture even before the gold rush had ended. The books and poems by Jack London and Robert Service and a string of feature films through the decades recounted how easily death came in the unforgiving wilderness of the Yukon.

The End Of The Klondike Gold Rush

By 1899, the Yukon Territory was filled with broken dreams. Stampeders who had dreamed of riches scraped by as common laborers in Dawson and the nearby mining camps. Though labor shortages meant that the pay was five times the rate back home, exorbitant prices ate up anything they earned.

Beachside Gold Rush west of Anvil Creek (1900)

Beachside Gold Rush west of Anvil Creek (1900)So when news arrived of a massive gold strike at Anvil Creek on the west coast of Alaska, all of the Yukon Territory was electrified. After news that even the beaches near Anvil Creek were full of gold and did not require a claim stake, Dawson City was depopulated seemingly overnight. The beachside tent city at the mouth of Anvil Creek exploded with newcomers. Soon, wooden buildings replaced the tents, and the city of Nome was born. Thousands of people moved from Dawson to Nome, transferring the title of largest city north of San Francisco with them.

Those gold mines that remained in the Klondike became large, mechanized operations using high-pressure hoses to blast the soil from the riverbank for sluicing, and steam to thaw the permafrost to follow the gold veins underground. For the individual gold seeker, the Klondike Gold Rush had ended.

The opinions and forecasts herein are provided solely for informational purposes, and should not be used or construed as an offer, solicitation, or recommendation to buy or sell any product.

Steven Cochran

A published writer, Steven's coverage of precious metals goes beyond the daily news to explain how ancillary factors affect the market.

Steven specializes in market analysis with an emphasis on stocks, corporate bonds, and government debt.